A systems science analysis of climate change advocacy

Failure of government in addressing climate change has fuelled social movements focused on climate-related policy and action across the globe. As the most significant public health issue of the 21st century, tackling climate change is fundamental in addressing human health worldwide.

To date, most research has focused on the types of strategies used by climate advocacy groups and how they frame the problem. Examples like lobbying campaigns, rallies, petitions, blockades, boycotts, and other tactics, have undoubtedly helped raise vital public consciousness at a local level.

From a message framing perspective, research has overwhelmingly focused on ‘diagnostic framing’ — what the problem (climate change) is represented to be — rather than ‘prognostic framing’ — the proposed remedy for the problem.

There’s little known about how climate advocacy groups are framing their political demands, an area of high importance when working to influence large-scale change.

Why is it important to analyse the political demands of climate advocacy groups and how did we do it?

Not all policy demands and actions have the same potential to create the changes needed to mitigate climate change. So, it’s important to understand to what extent different demands have the leverage to create change in the system.

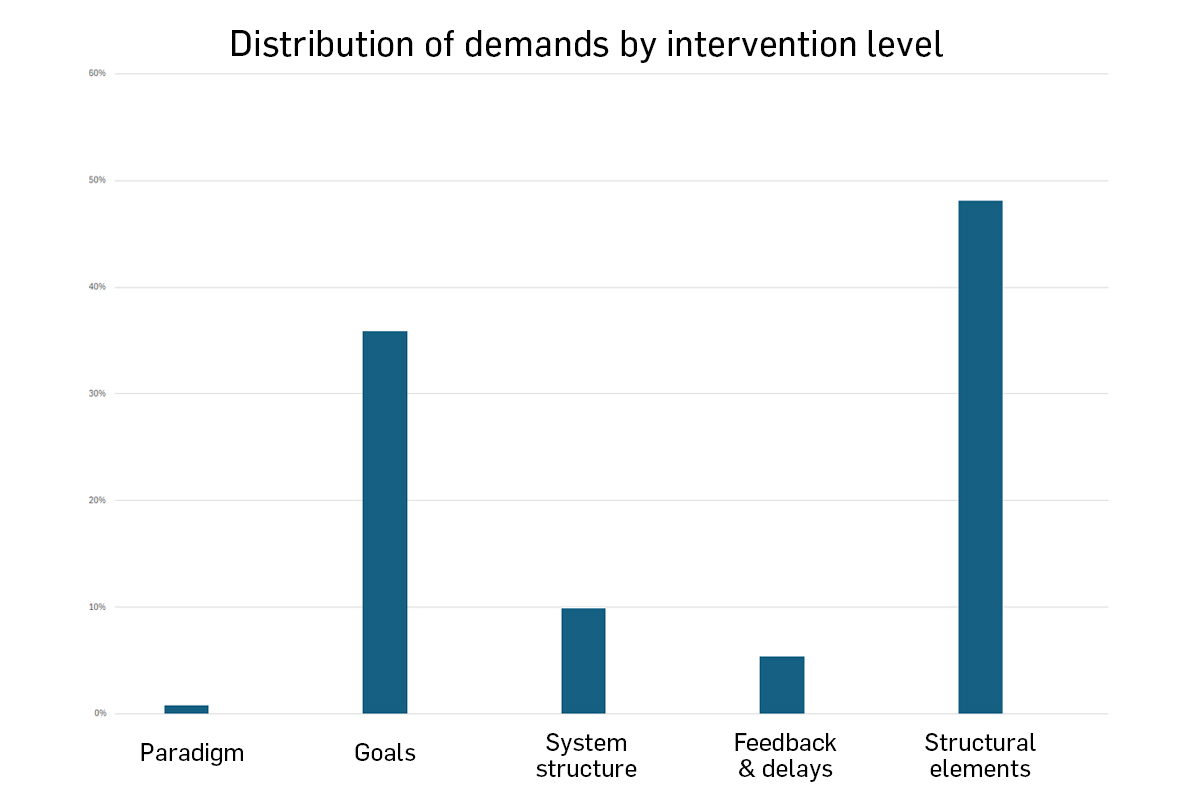

Using the Intervention Level Framework (ILF), a systems-science tool used in health promotion and public health, this research analyses 131 political demands from 35 different climate-related advocacy groups in Australia.

The ILF aims to provide a deeper and more cohesive understanding of the most effective ways to address complex problems. It provides a method of identifying specific interventions which are most effective at producing large-scale change.

By unpacking the types of leverage points for change most commonly mentioned by climate advocacy groups in Australia we can identify which are missing and assist groups in choosing demands that might be more impactful in leveraging change.

Results

Results show demands are more focused on lower system leverage points, like stopping particular projects, rather than more impactful leverage points, like the governance structures that determine climate-related policy and decision-making mechanisms.

For example, the majority (57.3%) of demands were categorised as ‘general’ which includes things like:

- Levels of pollution

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- Keeping global temperatures below 1.5°C

Within this category, there was a lack of focus on any specific policy interventions which could be implemented by governments.

As well, the results highlight the lack of attention on public health related topics of transport and food systems.

13 demands (9.9%) were coded at the level of system structure, which is far fewer than structural elements (63 demands, 48.1%). However, changes to systems structures have the potential to be far more impactful leverage points than structural elements.

Middle leverage points like decision-making bodies and monitoring systems can be very important in creating system change. This is because they are easier to achieve than changing goals or paradigm, but are more impactful than interventions at the level of structural elements.

Drawing attention to the lack of demands at these levels might help advocacy groups in formulating future demands that could better leverage change.

Access the research paper

This research ‘A systems science leverage point analysis of climate change advocacy’ has been published in Health Promotion International.

More information: Using the Intervention Level Framework in the context of climate change advocacy

The ILF highlights five levels of intervention that range from strong to weak leverage points. These are:

- Paradigm: The system’s deepest held beliefs; gives rise to the system’s goals, rules and structures; hardest level to intervene but can be most effective.

- Goals: Targets conforming to the system’s paradigm; need to be achieved to shift paradigm; interventions at this level can change the aim of the system.

- System structure: All elements that make up the system as a whole including subsystems, actors and interconnections between these elements; interventions at this level can change the entire system structure through changes to system linkages or incorporation of novel elements.

- Feedback and delays: Allows the system to regulate itself by providing information on the outcome of different actions back to the source of the actions; interventions at this level can create new, or increase existing feedback loops; adding new feedback loops or changing feedback delays can potentially restructure the system.

- Structural elements: Subsystems, actors and physical elements of the system; interventions effect specific subsystems, actors or elements of the system; easiest level to intervene but many actions at this level needed to create system change.

With a focus on Australia, due to its poor record on climate-related policies and the large number of advocacy groups, data was first summarised on the basis of categories of intervention.

Category of intervention | Number of individual demands listed |

Energy, fossil fuels, renewables | 36 (27.5% of all demands listed) |

Food, agriculture | 4 (3.1%) |

Land clearing | 11 (8.4%) |

Population growth | 1 (0.8%) |

Transport | 3 (2.3%) |

Waste | 1 (0.8%) |

General eg. Levels of pollution, greenhouse gas emissions | 75 (57.3%) |

The next stage in the analysis involved coding the demands against the ILF. Here are some examples of climate change related policy demands coded across the five intervention levels.

Policy demand examples |

Intervention level: Paradigm

|

Intervention level: Goals

|

Intervention level: System structure

|

Intervention level: Feedback and delays

|

Intervention level: Structural elements

|

Access the research paper

This research ‘A systems science leverage point analysis of climate change advocacy’ has been published in Health Promotion International.