Building trust, slow innovation, and private sector funds are key in evolving social impact

UNSW Centre for Social Impact spoke with Dr Michelle Darlington, Head of Knowledge Transfer at the University of Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation, on her October visit to Sydney. This visit was part of the newly launched 5-year collaboration between UNSW CSI and Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation (CSI) “that has the aim to increase learning and sharing about the latest research and innovations in social impact practice”, says Director of UNSW CSI, Professor Danielle Logue .

How has social impact as an organisational priority evolved and how is the research and education work of the Centre for Social Innovation at Cambridge University reflecting these changes?

Social impact has always been an organisational priority for us. An essential first step in having an impact is understanding the context in which you want to have that impact rather than thinking you know what it is and how to achieve it and trying to parachute in, which can be destructive rather than impactful.

We assist social start-ups by helping them build a theory of change model and to devise a data strategy and impact measurement strategy around that. If they’re a new start-up we help them identify the key impactful activities they do. We also help them devise financially sustainable business models.

We’re careful to differentiate the way we define impact in relation to other parts of the business school in the sense that we value the idea of scaling impact via disseminating knowledge or supporting other organisations through the diffusion of innovative ideas rather than purely organisations growing and scaling in size. We think open sharing of learning is important within the community of social innovators – we’re not competing we’re trying to achieve the same things.

Historically you can see a precedent for that in the cooperative movement who have as one of their basic principles educating other organisations wanting to be cooperatives in how to do that freely and openly.

What are some of the innovative ways that students, particularly those schooled in traditional business models (CEOs) are integrating social impact into their work?

We had one alumnus, a Brazilian student, who was working with a social innovation lab at CERN and writing about this idea of a slow innovation process and why it needs to be slower. In her research she looked at the ways in which innovation labs do social innovation because there’s perhaps a disconnect between what you might expect an innovation lab to do, if you’re traditionally from a tech or business space, and what social innovation is – which is often not that type of innovation.

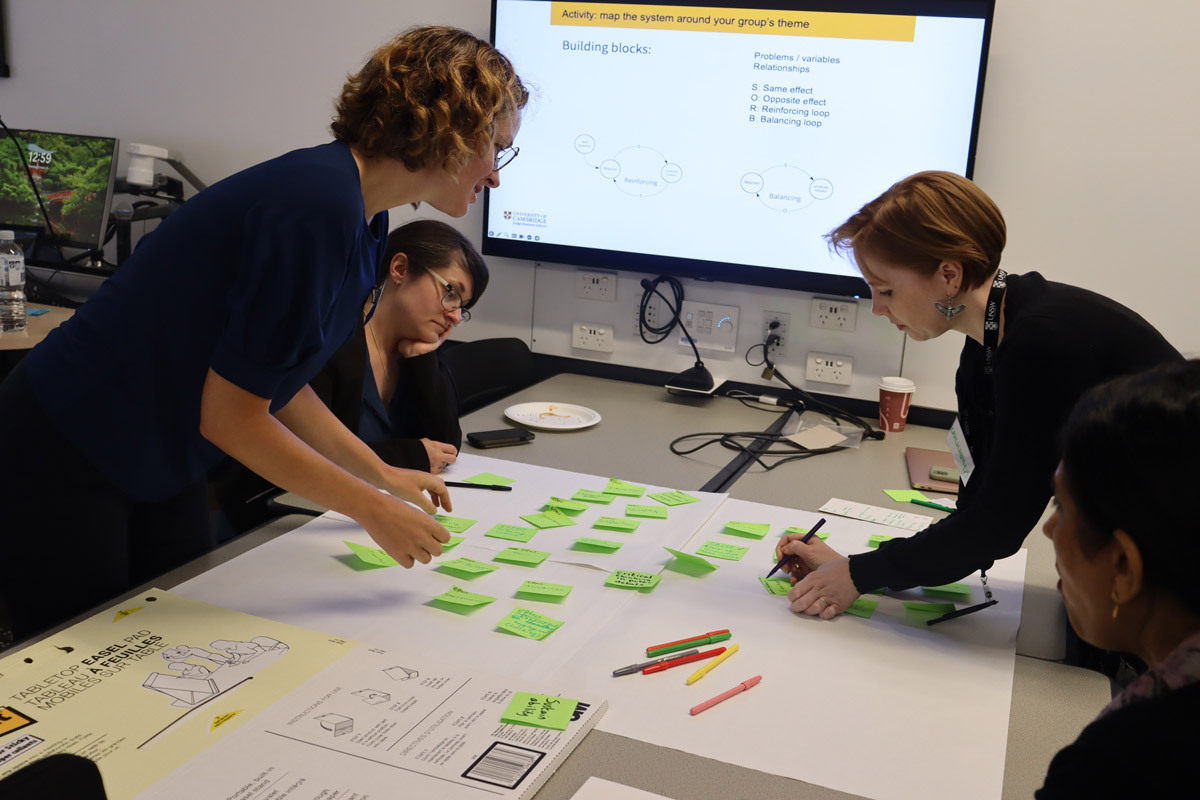

She describes what they do in discursive workshops where they take people from different levels of an organisation then bring them together with a flatter structure. You might have a director of a company, a middle manager and someone who works in operations having a conversation about solutions. That’s valuable because those people have different insights about what’s going to work, what’s feasible and what will be the consequences of what those in the group are proposing.

They’re not using the same language, so conversations need to be ‘slow’ and they require a level of trust building. When you have people from different levels of an organisation there’s also an expectation about seniority or whether it’s appropriate for someone more junior to speak. One of the things she explained they do is send people on paired walks to build trust and familiarity. Those exercises might sound superfluous but they’re actually vital when it comes to doing social innovation.

Your latest research project has seen Cambridge University work with the US Air Force in Montgomery, Alabama. How did the concept for this partnership come about? And what made the city of Montgomery an ideal place for exploring social innovation?

The partnership was initiated around 10 years ago by an individual who moved to Montgomery who’s been actively wanting to disruptively innovate in the air force. If you don’t have an individual who’s championing change within an institution, change isn’t going to happen.

An obvious reason why Montgomery is a good place to do this is because of its heightened reality in the sense that a lot of the inequities that we see happening everywhere – education, health, economic, racialised inequities – all of them are present and it's quite charged as it has this rich history. It was a centre for both the slave trade and the civil rights movement. The other thing that makes Montgomery an ideal place is there are community members who are motivated to do something. They’re very active and continue with that social justice, civil rights spirit even if the history books would have us think that all fizzled out in the 1970s. One example is the Kings Canvas, an organisation which is actively drawing on the heritage of Montgomery, and evolving it culturally through community engagement in the arts.

When you do this type of collaborative work, what methodological approaches do you suggest?

The most important thing about this work is relationships – not sure if that’s a methodological approach – but I think it’s more important to build a trusting relationship between different partners than it is to have a process that works. If we didn’t have trust, then nothing that we’d do would work.

Also, taking the time to deeply understand the context of the place before thinking that we have anything that even resembles a solution. If I’m facilitating a workshop, I try to create a space where each person can bring to the table something that’s important to them. People have to feel seen and heard and they have to feel they have skin in the game. Otherwise, they’re not engaged. How to enable that is a question I keep experimenting with.

“If we didn’t have trust, then nothing that we’d do would work.”

Cambridge CSI runs the incubator programme, which helps social enterprise start-ups get off the ground. How would a traditional corporate organisation best support an incubator-style enterprise?

As a corporate there are significant obstacles to investing in social businesses and the danger is that that relationship is a power imbalance. If a large organisation is investing in a smaller one and is wanting a big return, they can be pressurising that smaller one to scale too quickly. It can create mission drift and cause them to compromise what their original purpose was, which is something we’re wary of in how we support new businesses that are socially oriented.

If a corporate genuinely wanted to support social enterprises they can go two ways about it, ideally. One is to acknowledge the imperative for growth, scaling and high return and only support social businesses that have the potential for that, which is a small segment of social enterprises. Or acknowledge the fact that some of the enterprises they support are not going to scale or have a high return on investment and maybe sometimes those might cost them money. But at the same time, they can look at the social return on investment that those organisations are generating.

One example of a social enterprise from our incubator programme is a chocolate making business called Harry Specters. They employ staff with Autism. Part of their social return on investment can be calculated as respite for carers – something that can be calculated with a high degree of certainty and put in a spreadsheet. They can say, ‘If we employ this many people who otherwise would be in care, that’s creating this many hours of respite for carers’, whether public sector carers or parents, and that can be translated into monetary savings to the social services which is otherwise providing care for those people.

While the business doesn’t have a super high monetary return (they promise to use 51% of profits to benefit Autistic people), they accept investment. One initiative they have is chocolate bonds. So, if you invest in the company and rather than receive your dividends in money, they send you chocolate. After a while some investors were offered payment of dividends, but actually preferred their bonds in chocolate!

“A lot of the problems we’re wanting to address may seem localised but in fact they’re global problems.”

UNSW CSI and Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation just launched a 5-year partnership. Why are collaborations between social impact centres important?

Collaborations are important. And while understanding context is important, there are a lot of things we have in common that we can learn about from each other. A lot of the problems we’re wanting to address may seem localised but in fact they’re global problems. Widening inequities of all kinds, this is happening everywhere, and that’s not a coincidence. For social impact centres it’s important for us to remember that we’re not competing for this space, there are plenty of social problems that need to be solved.

In your view, where is the practice of social impact heading?

I can’t see us having a revival of the type of government-led social programmes that we saw in our parents’ generation. Therefore, [social innovation] has to come from somewhere and that’s going to be the private sector largely and charities will have to rethink more and more their business models – how they are generating income to think about trading activity. It's a potentially exciting field.

In the UK there’s growing interest in social impact work in the private sector partly because public and social sectors are receding in social services provisions especially for the elderly, new families and those in poorer more marginalised areas. But I also think that the social problems we’re witnessing now compared to what they’re going to be in 5, 10 or 20 years are just the tip of the iceberg.

In terms of environmental crises, refugee crises, widening inequities, forced migration of people... all these things are going to hit us hard. We need to be prepared for that and to stop operating as business as usual – that’s what’s got us here.